In this article, we will examine the room for analyzing the “remember me” cookie with a brute force attack from PortSwigger Lab

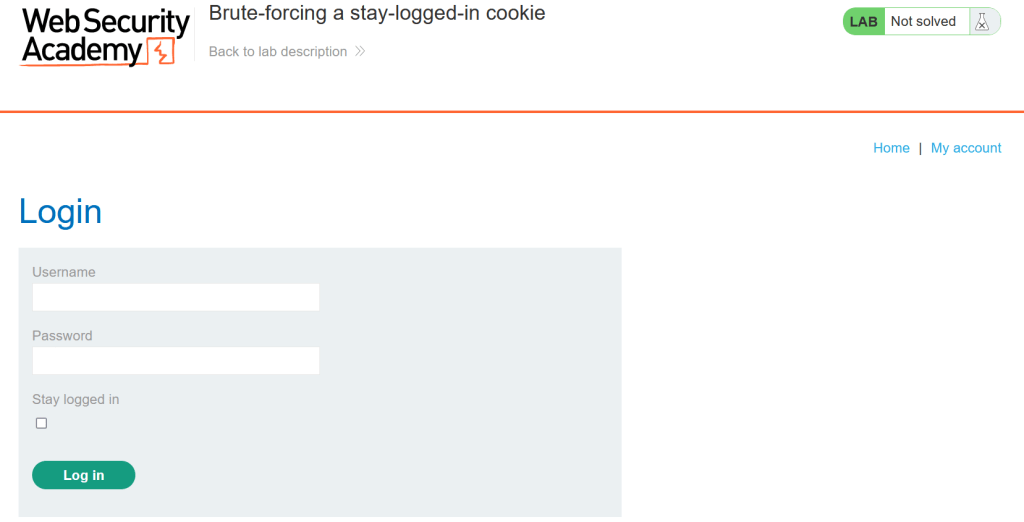

In this lab, the web application we will target has a “remember me” feature that keeps users logged in. To solve the room, we have a sample username and password, a target username and a list of words to use in our brute force attack.

We will use the username and password “wiener:peter” in our first interaction to familiarize ourselves with the web application and then we will try to get a valid session on the target user “carlos“.

Let’s get started.

Getting to know the target

When we click on the button to access the lab, we see a blog page. I’m not going to explore the whole blog as it’s very clear what we are going to do in this lab, but if you want to explore you are free to do so. In an environment where there are no instructions on what to do, the first thing to do is to explore the target. After of course opening the Burp Suite in the back and letting the requests accumulate.

First we’ll log in with the sample user credentials we have. If you want to make your work easier, if you log in by pressing the “stay logged in” button, you will also prepare the request we will use in a moment.

After logging in here, a simple panel welcomes us. The only function here seems to be to change the e-mail address. If this screen does not greet you directly, click on the “my account” button.

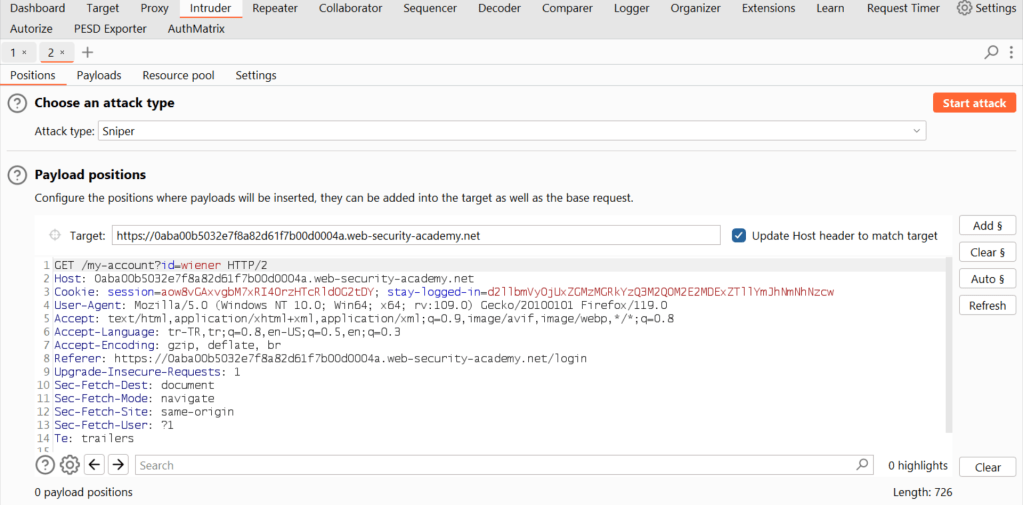

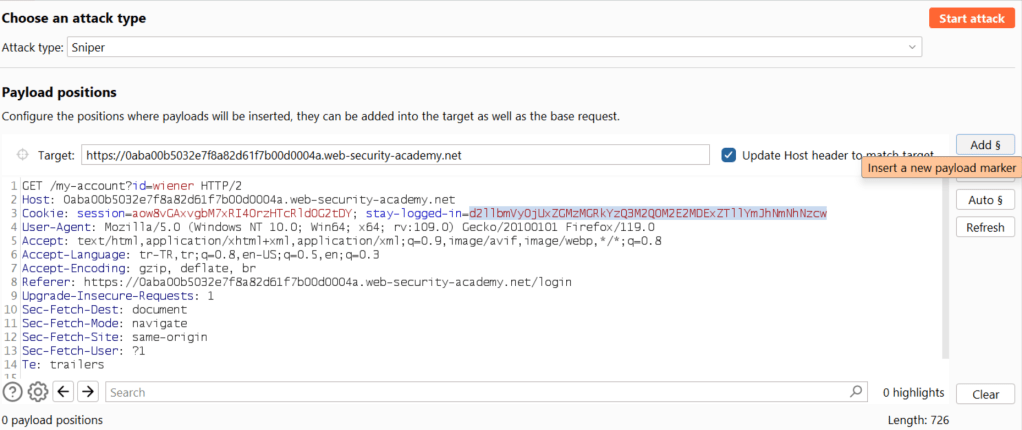

Then we will find the request to the “my-account” url with the GET method from our HTTP history and send it to the intruder feature.

At this stage we know where to target. Our target is this cookie, but first we need to understand how it works, so we need to do a simple reverse engineering process on it to learn the steps that make it up, i.e. the description of our cookie.

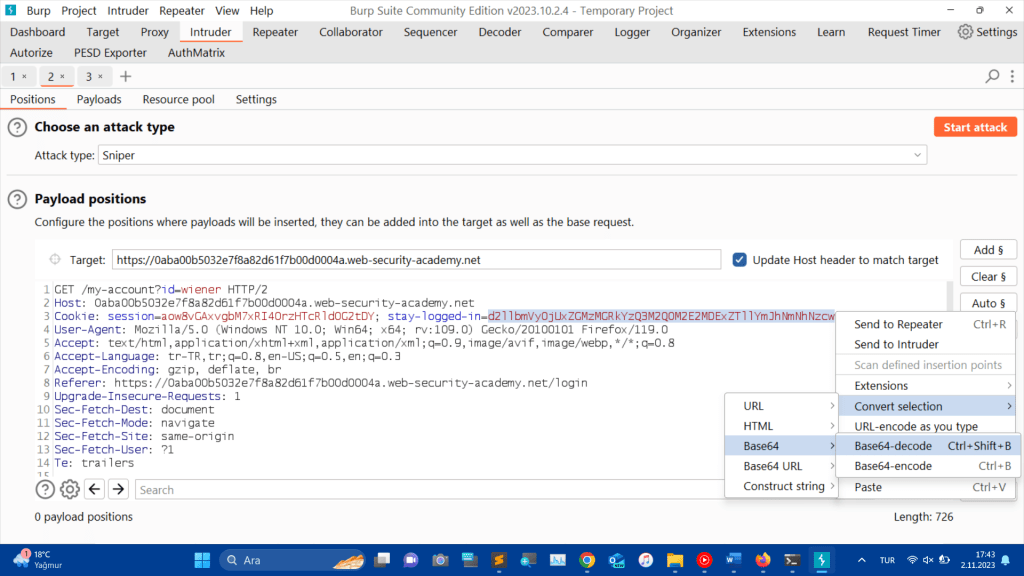

You can select the cookie, right click on it, hover the mouse over the “convert selection” button, hover over the “Base64” button and click on the “Base64-decode” button.

Or you can copy the cookie, paste it into the decoder property, click the decode button, select the base64 option and see the decoded version of my cookie.

In real life examples, the same technique may not work for every cookie. You can try to identify what type of string you have by using all the technology available to you. But some of your attempts may not be fruitful and that’s normal. Not every day is sunny.

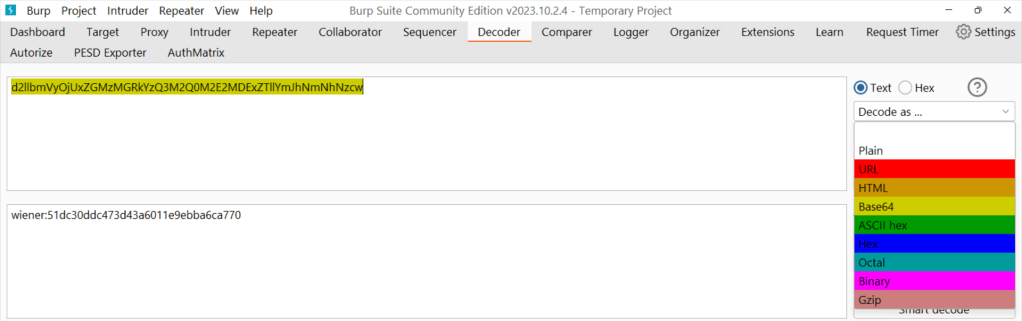

With this action, we have learned that the cookie is created as [“user_name:” + “characters”]. But what are the characters after the colon?

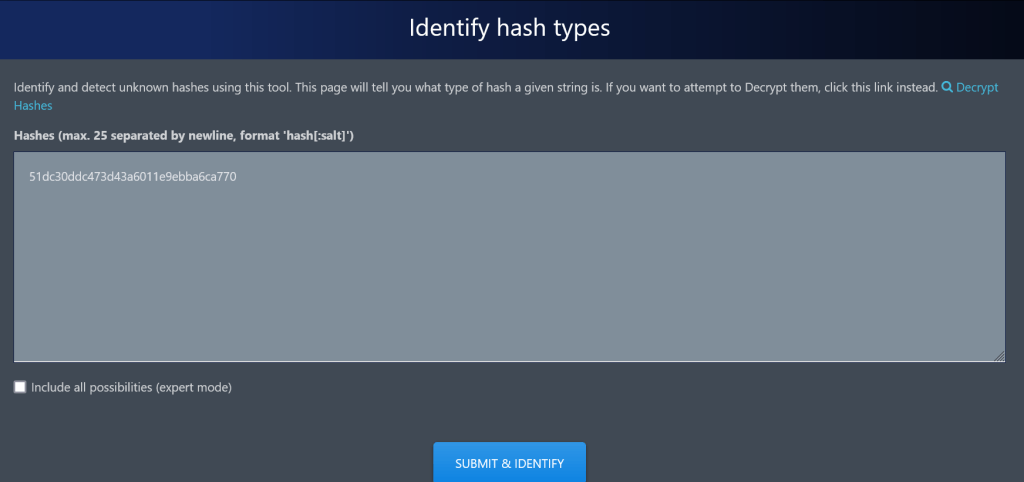

At this stage, I googled “hash identifier” and accessed the -hash identifier- (https://hashes.com/en/tools/hash_identifier) tool. When I queried it, it showed that it was most likely an MD5 hash.

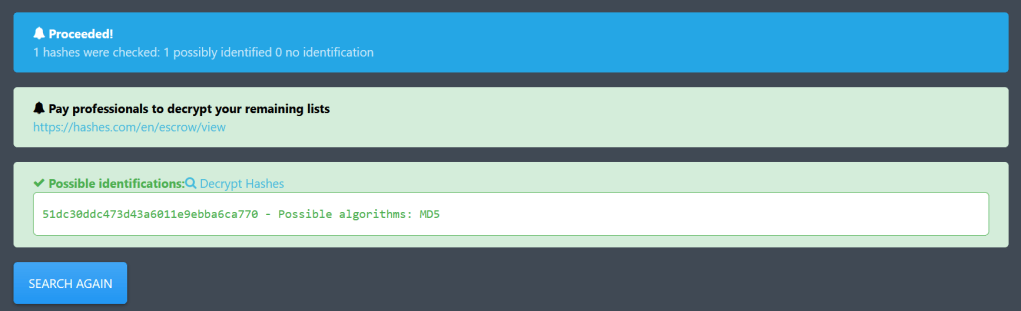

Since we know the password of our sample user, we have one word we can use to identify this md5 hash. When we get the hash of the word “peter” with the md5 generator tool, we see that the result matches the string of characters in our cookie.

As we understand from this process, the cookie that the application gives when the “stay-logged-in” button is pressed:

1.md5 hashing the password

2.user_name:md5_hashed_password

3.base64 encoding of the array

this process is getting executed. It has little security against a carefull analyze.

Creating cookies with username and password was an old practice. Today it is an unpopular practice that compromises security. Nowadays, it is a popular practice that cookies should be salted, even if they contain user-identifiable information, or created as single-use random characters, which is considered correct.

UNGA BUNGA – Throwing stones at the door

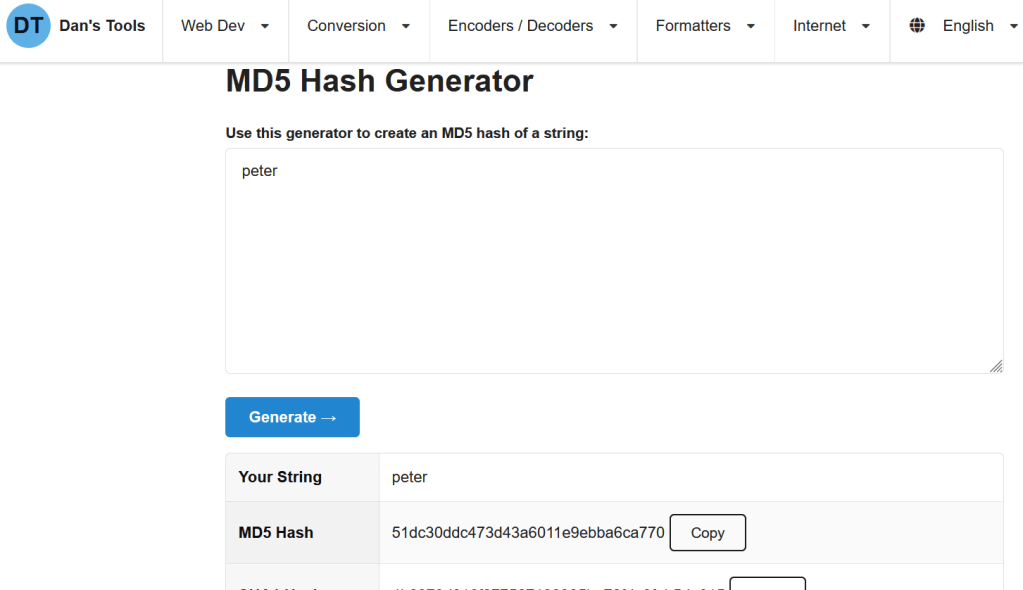

Now all we need to target “carlos” is his password to get a login. What if we skip the cookie and try a brute force attack on the login screen? After all, isn’t it better not to work hard, but to work smart?

The rate limit, which is somewhat ignored in many modern applications, has been applied here. Of course, this had to happen in order not to defeat the purpose of this room. So I don’t bother with this scenario any more.

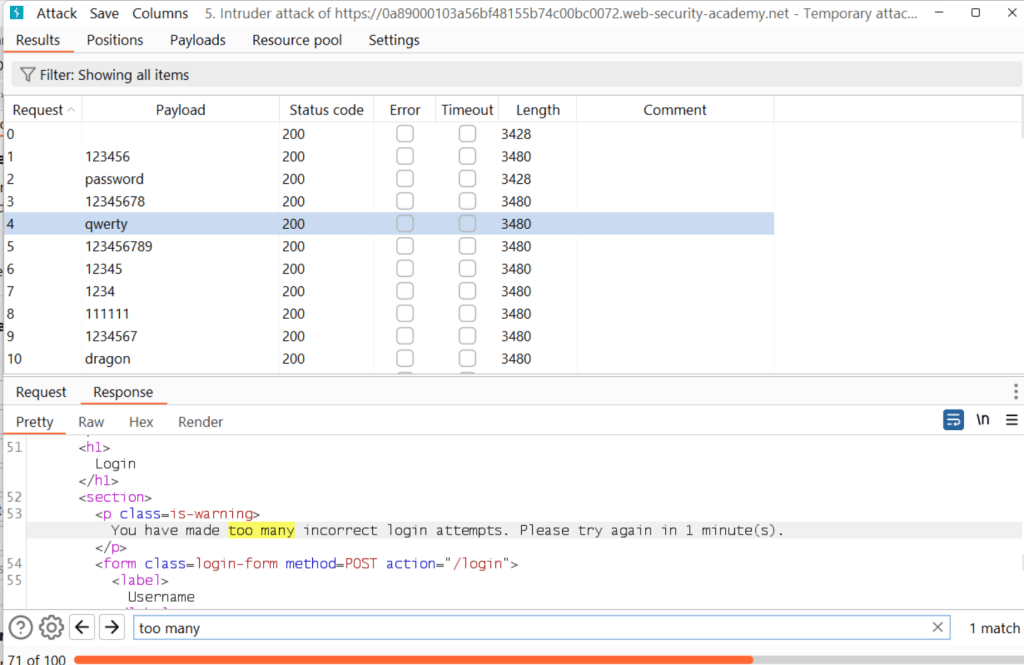

We are now back to where we left off in Burp. We’ll check the cookie in the “stay-logged-in=” descriptor of our request in Intruder, press “add” and mark it as our attack vector.

Next, we will bake our cookie. We have already discovered our grandmother’s recipe, let’s see how it tastes when we make it ourselves.

We go to “Payload settings” in the “Payloads” section of the Intruder panel and paste the sample list from Portswigger’s laba access page.

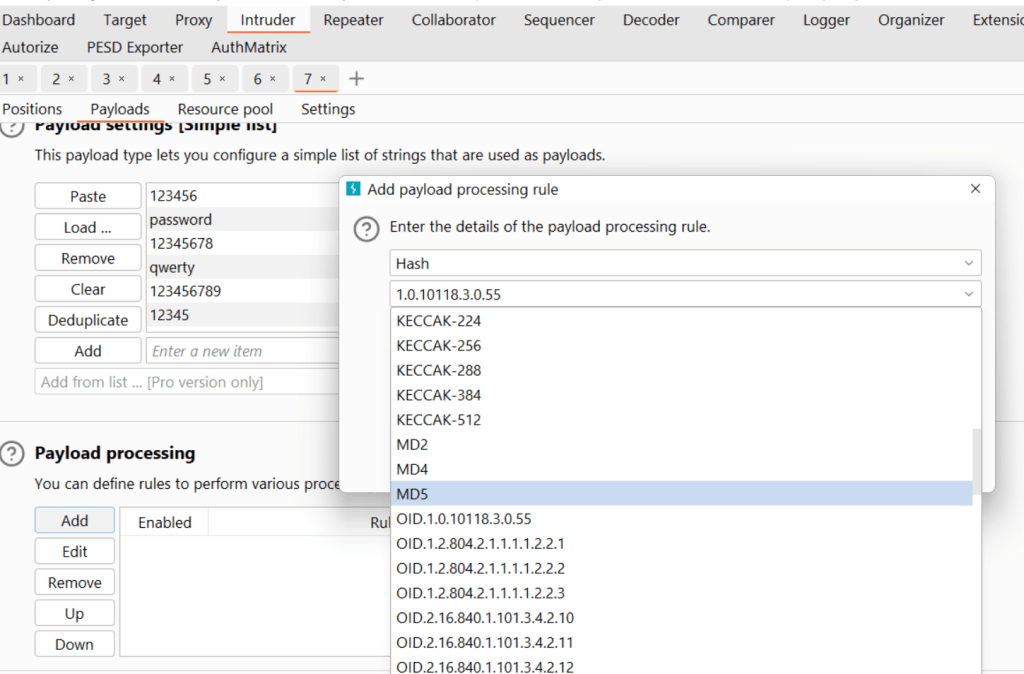

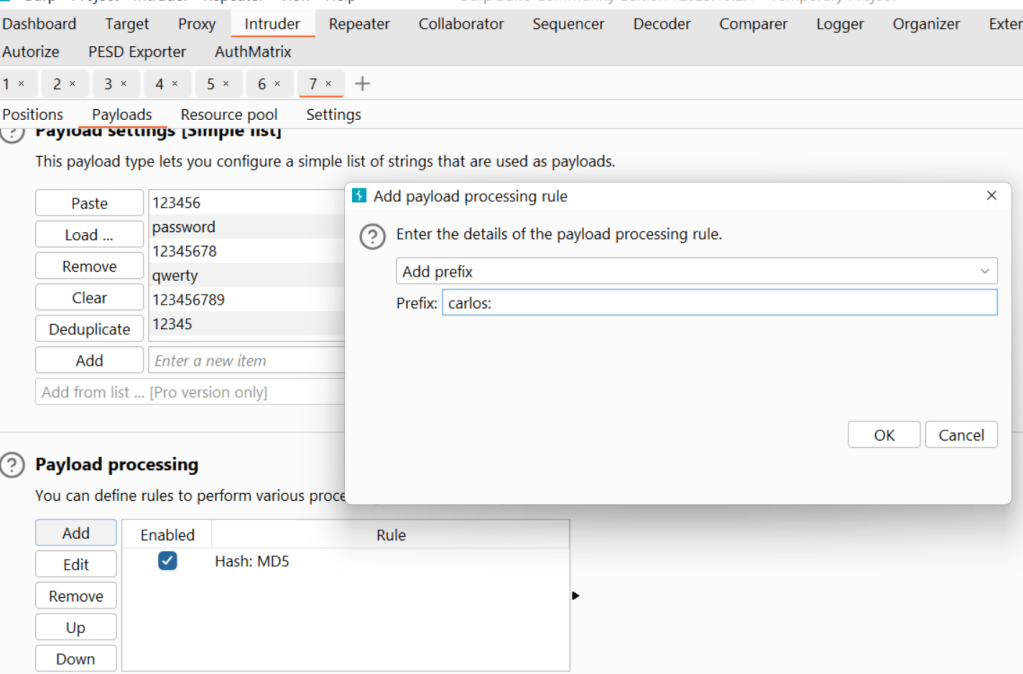

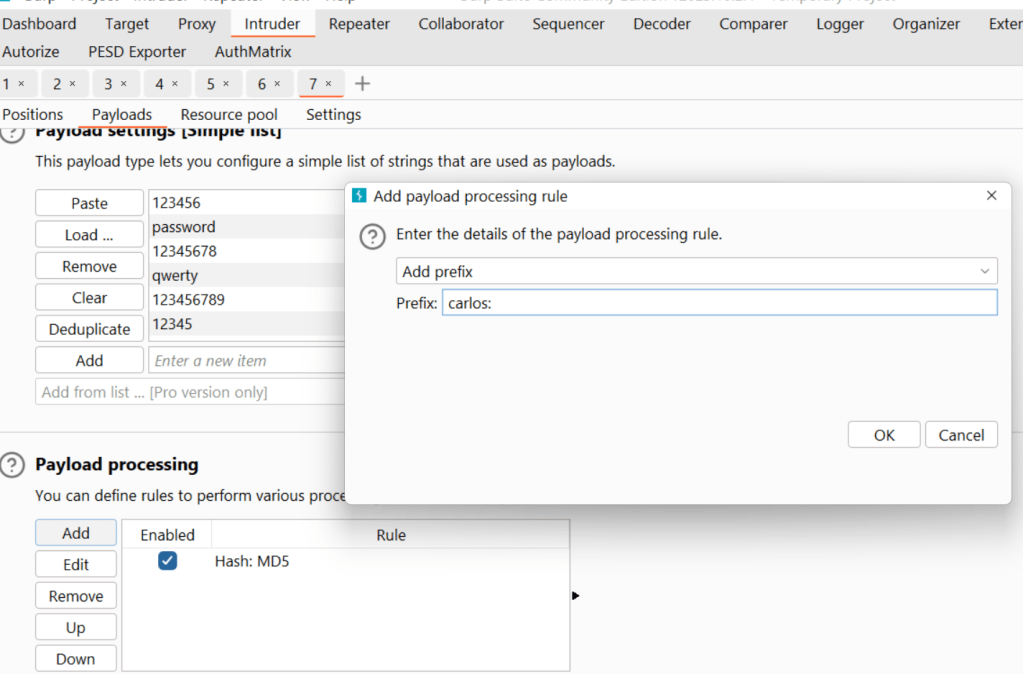

Then we go to the “Payload Processing” function just below it and define the modification tasks it will perform on the workload by following the order here.

Press the “add” button and select “hash” and type “md5”.

Press the “add” button and select “prefix” and enter “carlos:”

(to represent [user_name:])

(“prefix” means “add at the beginning”, “suffix” means “add at the end”).

Press the “add” button and select “encode” and the “base64-encode” button.

**-**–*

But what would happen if we didn’t follow this order?

Burp performs these actions by moving from the first task you add to the next (in a list from top to bottom). If necessary, you can change their order with the Up-Down buttons on the left. If we did not follow the order in the example, our description would not be correct.

- If you want, you can edit the prefix here to “wiener:” and add the payload list as just “peter” and try it on our first example user to see if our recipe is correct.

Finally, if you noticed, the page didn’t change much even after logging in. If you’ve ever wished that Burp had a customizable identification feature to distinguish the answers to requests, your wish has just been granted by Santa.

Finding Cinderella

In the settings section (“settings”) of the “Intruder” panel, find the “Grep – Match” feature and add the “Update email” warning there.

(It may be necessary to log out before launching the attack, not sure)

After launching the attack we will see a lot of requests, one of which is the magic combination we are looking for. Assuming that all but one of the requests will fail, if we can identify the indicators that distinguish that one from the others, we can easily find it with the filtering features.

You will notice that the failed requests will have the same status code or length. By clicking on one of them in the attack screen and changing the sort order, you can see the correct request as soon as it appears..

—If it gives errors and the status results don’t appear, the lab may also be having a temporary problem. It is natural to encounter such things, considering that this lab is relatively easy, if you are sure that you are doing everything right but you cannot progress (at least 10 minutes), take a break and try again later. Even though we live in a technological age, sometimes not every computer achieves the same result and this is normal when it comes to solving a lab.—

Extra notes:

- Being able to gain access by analyzing cookies or creating them from scratch is a security vulnerability. It may belong to the BAC category in general, but it should be analyzed and identified on a case-by-case basis.

- For example, in this example, we have performed the process of obtaining an unfair session by resolving cookies. But we did not bypass a defense mechanism for cookies. The first thing that comes to mind here may be “Broken Authentication and Session Management”. But I don’t think it fits this definition, because there was already no protective measure, so let’s talk about its inadequacy. Defining the structure of the cookie was extremely simple, effortless for someone familiar with this attack surface. If there had been a security measure in place and we had made an effort to bypass it, then it would fit into this category. “Server Security Misconfiguration” might come to mind as a remote possibility, but it’s far from an unplanned unjustified action on the server, so that’s not it either. Although it seems like it could be under the BAC category, I think it belongs to the category of “insecure design”. There is a rate limit in the login function, but not in the “my-account” request. It’s clearly an inconsistent architecture. The fact that “remember me” cookies are created in such a simple way, and that the same cookie is created every time, shows that security was definitely not at the forefront of the application’s design. For an application like this, it is likely that a solution would have been developed specifically for this finding and would have been just a brick in what should have been a wall.

-Copying and pasting a randomly generated cookie from another user and obtaining their current session is not a vulnerability. In fact, in modern applications, when “best practice” rules are applied, even if you copy and paste the cookie, it will not allow you to access the current session. But accessing it in this way is not considered a vulnerability today.

Remembering cookies stored on the user’s computer are an attack surface for application developers, even though they are not stored in readable form. But if you save your password in a word file and store it on your computer, it is your own attack surface.