What is a Race Condition?

In this age where everyone wants to get ahead of each other by accessing more technology, resources, and speed, speed alone does not mean anything. Or does it?

In this article, we will examine race condition vulnerabilities. Technically speaking, these vulnerabilities are condition-based weaknesses that can be manipulated depending on the speed at which a process is executed. They are actually quite interesting and involve compromising the security process by disrupting the workflow with very simple touches.

Due to the absence of appropriate locking mechanisms and synchronization between different threads, an attacker can exploit the system and perform an action multiple times, carrying out operations beyond their authorized scope.

Example of a Race Condition with a Record Addition Limit

Let’s imagine an application. This application has a registration function with a limit. Users are limited to adding no more than five entries. We will examine an example of adding more than five entries by exploiting a race condition vulnerability.

The approach in this example is the same as in other popular race condition examples, such as money transfers or gift code usage.

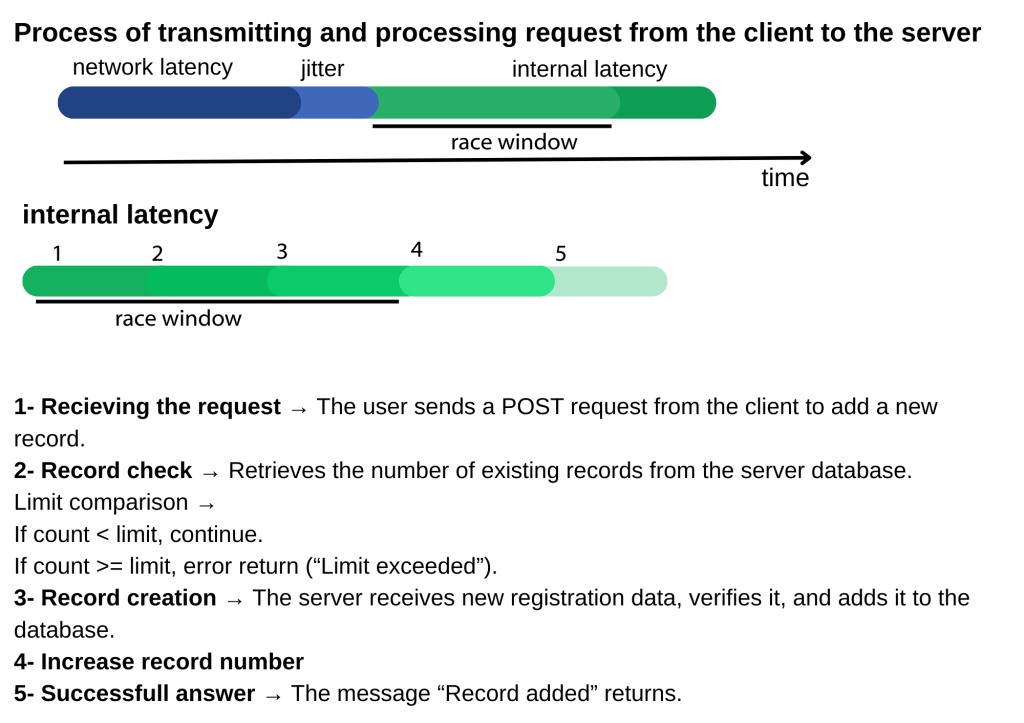

To understand speed conditions, we first need to understand the relationship between the client and the server.

Network latency: This is network delay. It is the total delay experienced from the time a request is sent from the user’s computer to the server.

Jitter: This is a variable arising from the uncertainty of network delay; it is actually a subcategory of network delay.

Internal latency: This is the total processing time of the operation on the server. Once completed, the output is sent to the user, again affected by network latency.

As we saw in the section on the process of transmitting the request from the client to the server and processing it, there are time intervals such as network latency, network latency uncertainty (jitter), and server processing time (internal latency) between the client and the server response. The time interval in which race conditions can occur is within the internal latency. In the following sections of this article, we will discuss how to use the Burp proxy to take advantage of this time interval and perform this without being affected by network latency.

Internal latency, in turn, is divided into subheadings based on the logic of a program’s operation. In this example, it is divided into five steps. Depending on the situation, it may contain more or fewer steps.

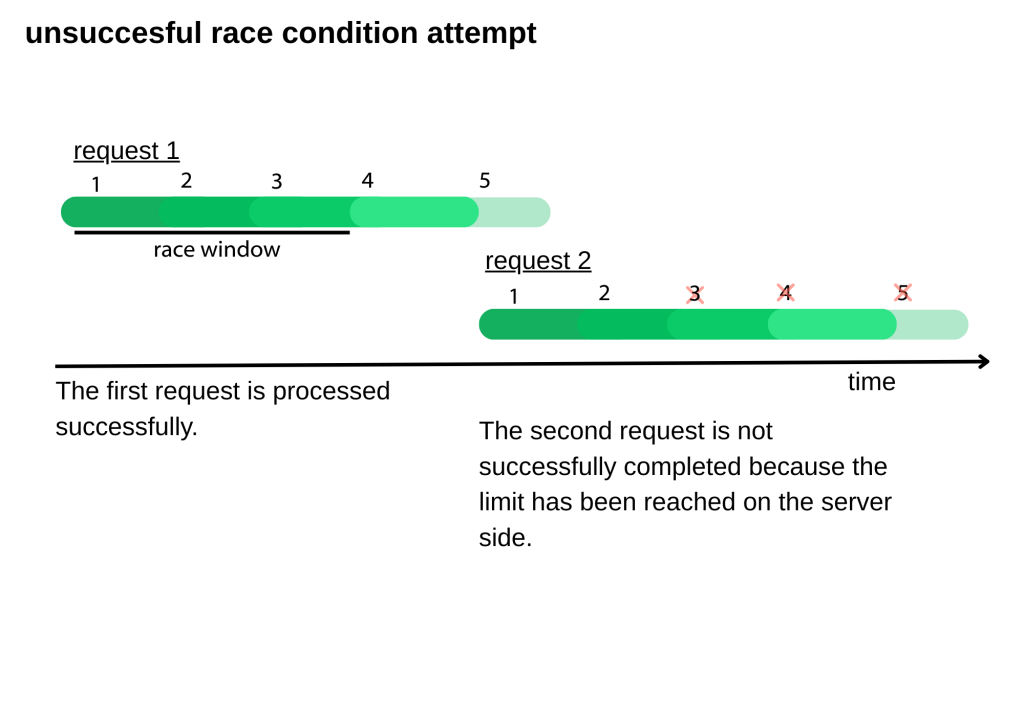

Here, we will examine a failed speed condition test. Let’s assume that we are in a situation where there is one record left before the record limit is exceeded. We will try to create more records than the specified limit by sending requests one after another.

In this case, if we send a request, it will be processed successfully because the limit has not yet been reached. Since the speed condition has not been customized to take advantage of the time interval, the second request will not be processed successfully because it will hit the limit. The second request, which begins processing after the operations that perform record control and increase the number of records within the processing time that causes the internal delay have been completed, will not be processed successfully. This is because when record control is performed, the response returned is that the record limit has been reached.

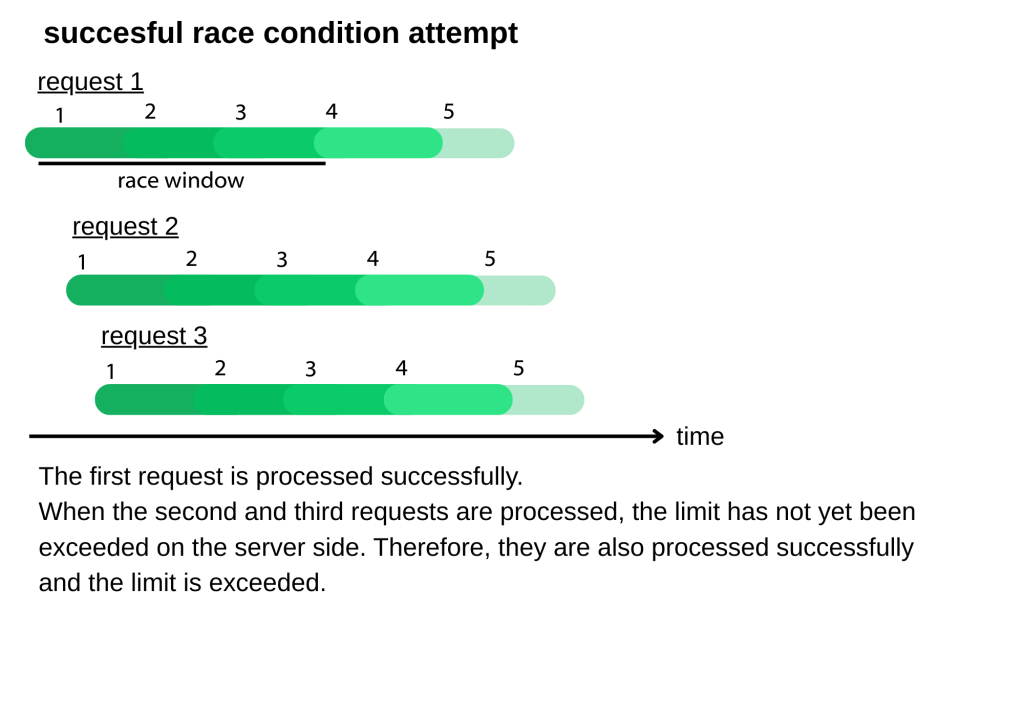

Here, we will examine a successful speed condition exploitation. As can be seen, in order for the requests to achieve their goal, other requests must have already begun to be processed before the number of records is increased. Since this process takes place in milliseconds, network jitter must be minimized. We will examine the features of the Burp suite proxy that enables this in a moment.

For the process to be successful, other requests must reach the server and begin to be processed at the beginning of the process that creates internal latency. Let’s examine this in detail; again, let’s assume that 4 records have been created and the limit is 5 records.

When the record check is performed for the first outgoing request, the number of records is 4. Therefore, the request continues to be processed. When the second request begins to be processed, the number of records is still 4 because the first request has not yet been completed. This situation also applies when the third request begins to be processed. When the processing of these requests, which take advantage of the short time interval required for this vulnerability to exist, is completed, the number of records has increased to 7. The request did not hit the limit while being processed because the number of records was 4 when all requests began to be processed.

As you can see from all these examples and visuals, only a very limited number of requests can successfully exploit this vulnerability within this short time interval. Requests outside this millisecond time interval will not achieve a successful result.

Let’s now look at the features Burp Suite offers for speed conditioning.

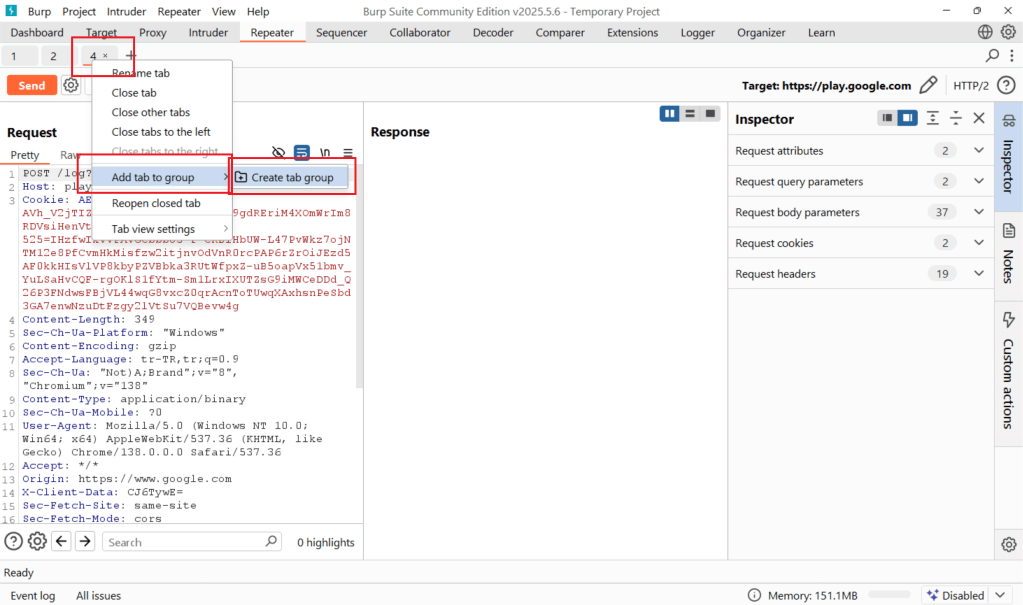

What is Burp Attack Group?

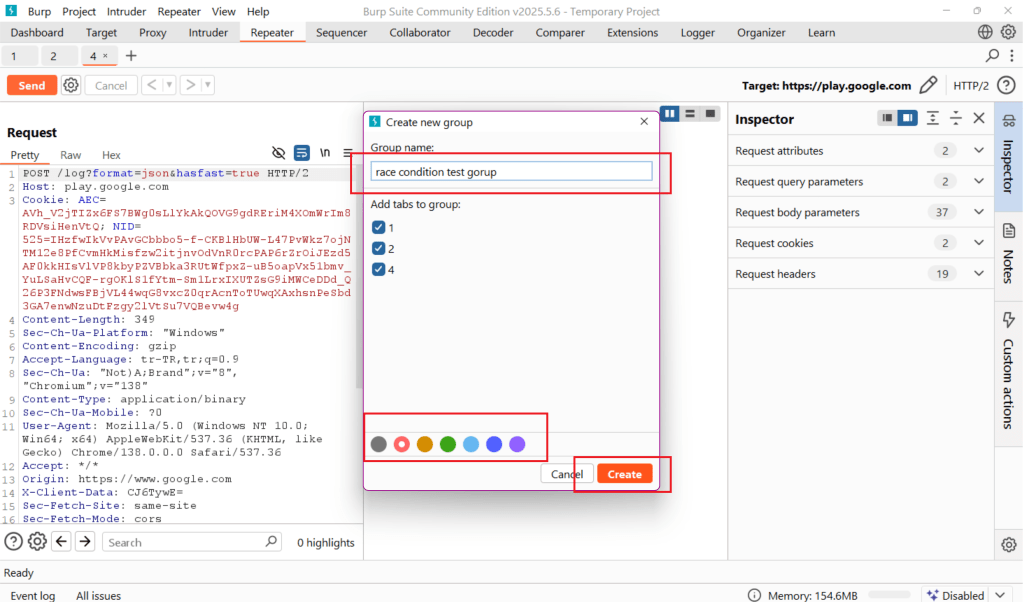

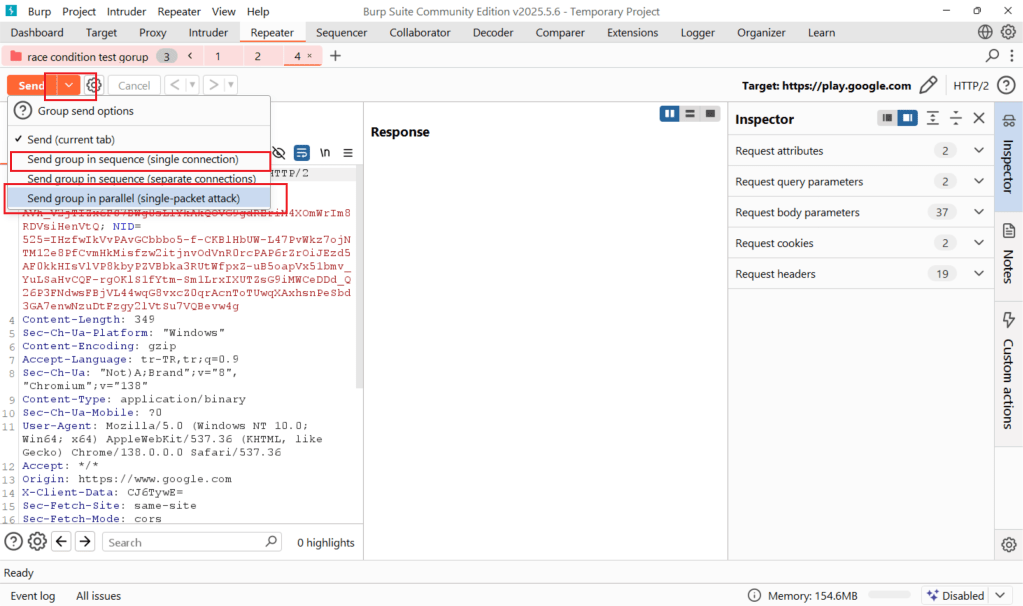

Did you know that you can use Burp Suite’s grouping feature to take advantage of various types of attacks? After sending requests to the repeater, right-click on any of the requests you want to group, select “Add tab to group” > “Create tab group.” Then, select the requests you want to include in this group and the color you want, and you’re done. Additionally, you’ll now see a dropdown menu next to the Send button. We’ll use this menu to take advantage of a special feature added specifically for race conditions.

What is Single Packet Attack?

A single packet attack is a method of sending multiple requests in a single TCP packet. This attack eliminates time differences caused by network jitter and ensures that requests are processed at the target almost simultaneously. To do this, requests are sent over a single HTTP/2 connection, a small portion of each request is delayed, and then the final parts are transmitted simultaneously. The operating system combines these parts into a single TCP packet, ensuring that all requests reach the target nearly simultaneously.

For more information about the Single Packet Attack, you can read Port Swigger’s article.

Single Connection Attack

In a single connection method attack, all requests are sent sequentially over a single TCP connection. However, requests are processed in sequence, meaning that they are processed very close to each other in time, but not completely simultaneously.

The goal is to test for desync (asynchrony) vulnerabilities caused by timing differences on the client side and to reduce the small delays that occur when establishing a TCP connection. This technique can be used to observe whether a race condition exists or not.

Is there no other way?

Of course not. As an example, the solution guides for this tryhackme room usually involve sending requests one after another via a Python script. Another example is when I accidentally discovered a race condition while sending consecutive requests with Intruder. The key feature required is the ability to send requests quickly and consecutively.

How to Prevent Race Condition Vulnerabilities?

A race condition occurs when multiple processes or pieces of code attempt to access a shared resource at the same time. To understand this situation, the concepts of exclusivity and atomicity are important. Exclusivity means that when a piece of code accesses a shared resource, other pieces of code must not modify the same resource. If another piece of code interferes with the resource, exclusivity is violated. Atomicity, on the other hand, refers to a piece of code operating as a single unit; that is, another process cannot access and interfere with the same resource in the middle of the code. If another piece of code can interfere with the shared resource and violates these two rules, a race condition has occurred.

Sequential Workflow

Sequential processing refers to the execution of operations or code fragments in a specific order, one after another. In other words, one operation cannot be moved on to another until it is completed; each step is processed in order and in a regular manner.

Atomic Operation

It means that a transaction or piece of code is indivisible and must be executed as a whole. When a transaction is atomic, no other transaction can intervene in the middle; it either completes entirely or is considered never to have happened.

Additional Resources for More Information

https://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/362.html

https://portswigger.net/research/the-single-packet-attack-making-remote-race-conditions-local

https://portswigger.net/research/smashing-the-state-machine#single-packet-attack